Photo by Jakob Owens on Unsplash

Drug market harms in social media drug markets

Robin van der Sanden, PhD – SHORE & Whāriki Research Centre, Massey University

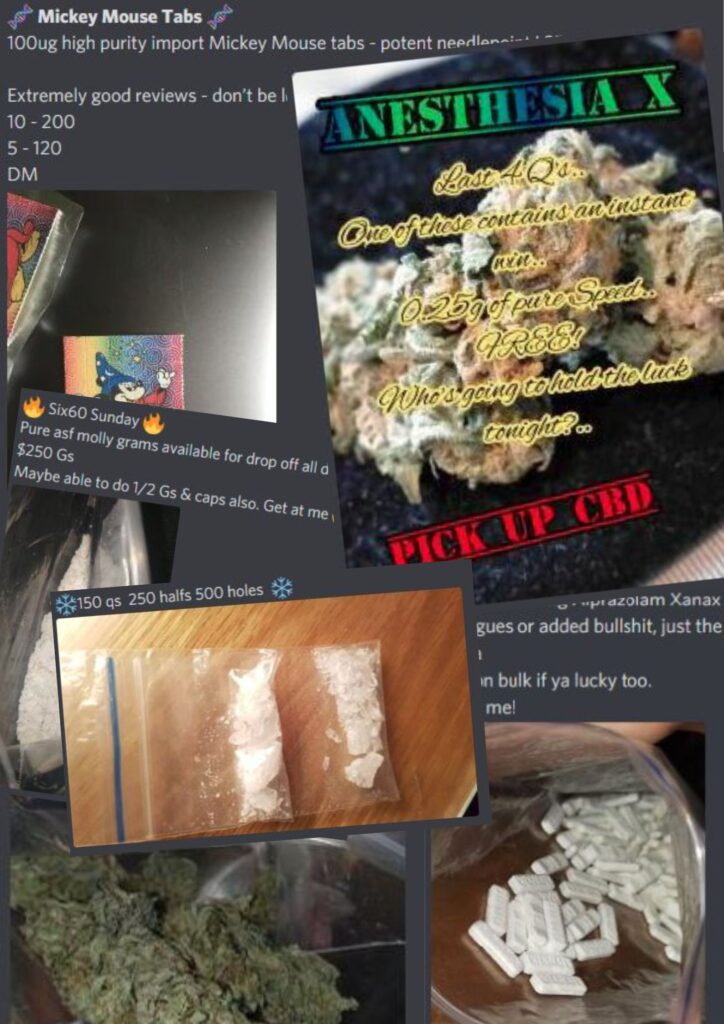

It likely comes as no surprise to Bluelight’s readership to hear that social media and messaging apps increasingly serve as sources of drug access, especially among younger age groups. You may have used them for this purpose yourself, or at the very least, know of others who have. Perhaps you’ve stumbled across drug dealers advertising their wares on Snapchat, or underneath Instagram posts. Or maybe you prefer the more competitive, fast-paced selling groups, such as those on Discord, or Telegram. You might even be reading this as emoji-dotted messages dance across your phone screen offering you MDMA fresh from the darknet, or someone’s unwanted benzodiazepines.

The appeal of social media and messaging apps as points of drug access is straightforward: they’re familiar, used by over half the global population, contain lots of handy features like self-deleting messages, and provide some level of discretion and security. They’re also conveniently located on portable smartphones, and most importantly – they make networking a breeze. In short, it makes a lot of sense to use social media and messaging apps to buy drugs. For many, they make buying (and selling) easier, faster, and more convenient than ever before.

The climate of easy drug access that can be characteristic of social media drug markets, and their popularity among young people is of increasing concern to policy makers, harm reduction practitioners and researchers alike. Not only do social media drug markets make it easier for people to buy drugs, they may also change how people, particularly younger age groups, are ‘initiated’ into their local drug markets by making dealers more accessible. This is important because many young people and teens have traditionally relied more heavily on “social supply”, or drug access via friends and social connections. Social supply is often linked with reducing drug market risks due to the importance of friendship as a safeguard of product purity and trustworthy behavior. Taken together, these factors point to the potential for increased harm to young people buying via apps as they are pulled into higher risk drug markets more easily than in the past.

These concerns can be particularly warranted in social media drug markets that involve buying from (and selling to) strangers. For example, in the US, Snap Inc currently faces a series of lawsuits to determine its role in an increasing number of overdose deaths among teens and young people who bought counterfeit fentanyl-laced pharmaceuticals from anonymous Snapchat dealers. In cases where local selling groups bring many people together in one place they can serve as ‘melting pots’ that connect different players in a local drug market, with sometimes volatile results. With many group members presenting themselves anonymously, group ‘admins’ (if present) might not always have a handle on who is who. In New Zealand, this played out on large, easy-access Discord drug servers, where server admins struggled to keep scammers and gang prospects from entering the servers and causing havoc.

It’s worth noting that social media and apps, though easily able to be used to buy and sell drugs, aren’t exactly designed with this function in mind. This means many large, competitive social media drug markets, or anonymous seller profiles lack features that help incentivize trustworthy behavior between strangers, such as the review and mediation systems characteristic of darknet markets. Various community-based types of feedback systems have been reported in relation to social media drug trading (e.g., leaving comments under a dealer’s posts on Instagram, or posting scam warnings to a selling group). But these are limited in their effectiveness, especially when transactions are still largely completed in-person. This means ‘anonymous’ social media drug markets often leave people lacking both the support of app features incentivizing buyer/seller accountability and leave them without the most traditional form of drug market protection: social networks and mutual connections.

This is where the ‘flipside’, if you will, of social media drug trading comes in. Though social media apps may not be designed with anonymous drug trading in mind, they are designed to help us stay in touch with others around us, often helping us create expanded online versions of our offline social networks. This also means that they can be used to leverage an expanded local social supply market with associated benefits of greater choice and convenience while avoiding the increased risk of transacting with strangers.

Interestingly, besides perceptions of social media drug trading as higher risk, people have also reported perceptions of social media as ‘safer’ than alternative local supply options, citing increased transparency and accountability in local drug trading. Behind this perspective sits a social media drug market rooted in social supply, and its larger, more serious cousin – social dealing (think larger amounts of drugs and higher profits, but still primarily involving people defined as ‘friends’). In these cases, buyers and sellers use social media to expand drug access through social network-based channels, using regular social media behaviors like ‘stalking’ a potential drug connection’s social media profiles or using a messaging app to combine different networks of ‘friends’ to buy, sell, or swap drugs in a broader market while keeping added risk to a minimum.

Drug market researchers have argued that different types of online or offline drug markets have a range of impacts on both increasing and decreasing different drug market harms. This statement also holds true in the case of social media and messaging apps. While it’s difficult to dispute the fact that increased drug-related harms are part of the social media drug market picture, there’s also a risk of ignoring the potential harm reduction benefits of the often-overlooked world of social supply. Yes, dealers have never been easier to contact, but neither have your friends.

Editor’s note: Just a reminder that, as per the Bluelight User Agreement, we do not allow Bluelight communities and channels to be used for sourcing drugs.

Robin van der Sanden completed a PhD in Public health with SHORE & Whāriki Research Centre, Massey University in 2023. Her research explores intersections between social media, drug use and drug trading.